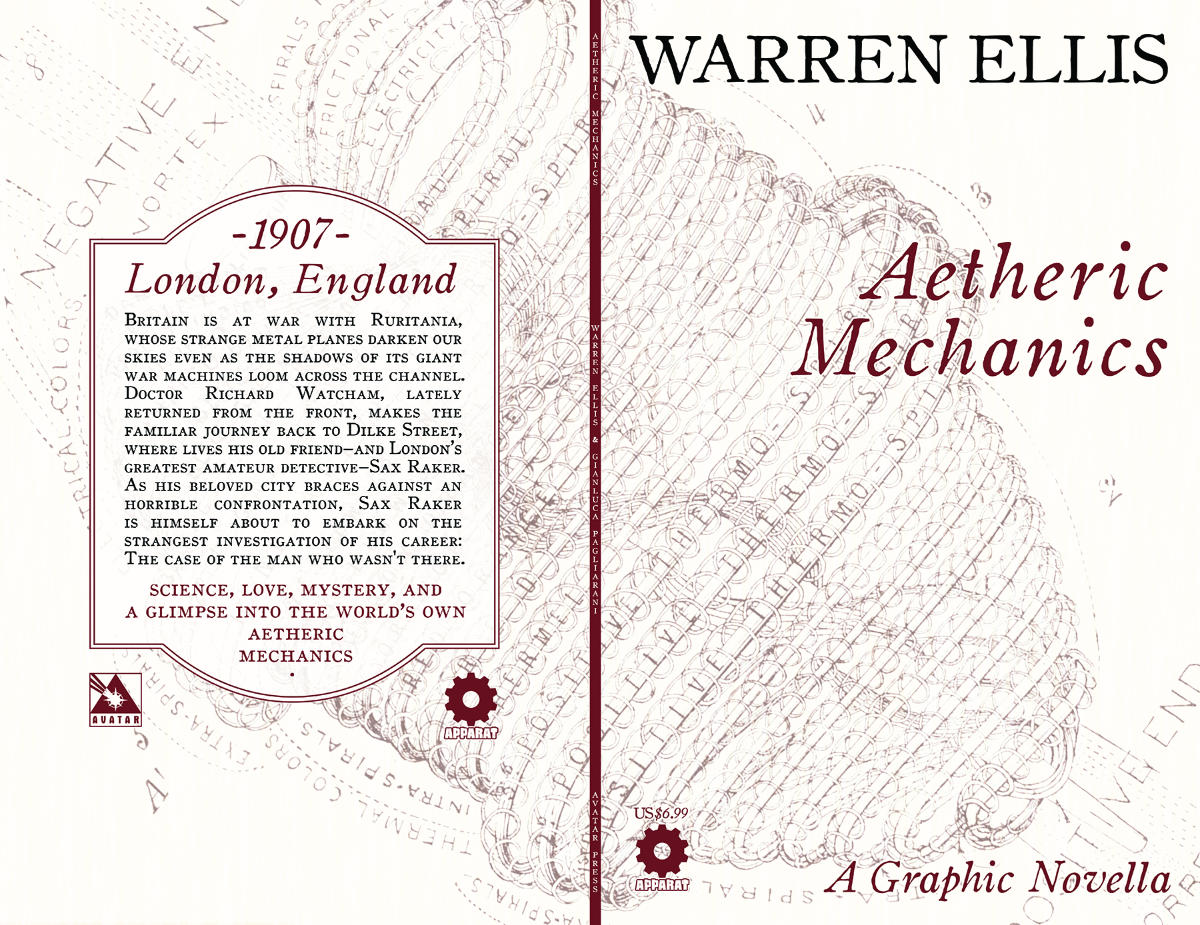

By Warren Ellis and Gianluca Pagliarani

This might be a week late, but I wanted to talk about Ellis’ graphic novella from Avatar (under his Apparat label), Aetheric Mechanics. The basic premise is Ellis’ version of Sherlock Holmes – this is a good thing: I remember an Ellis-written draft of his take on Holmes and Watson, in his unique style, which had an excellent grasp on the characters and even made Watson an ally worthy of Holmes, rather than a bumbling idiotic sidekick (I wish I could locate it to provide an excerpt – it had Watson meeting Holmes in a hospital where Holmes is bashing a fresh corpse just to see what the bruises would be like).

London, England, 1907. Britain is at war with Ruritania (the fictional central European country from Anthony Hope novels of the late 19th century, which has been used in other fiction since). Doctor Richard Watcham (our Watson analogue) has returned from the front and returns to his lodgings in Dilke Street with Sax Raker (our Holmes analogue); there is even a Mrs Hudson, Mrs Archer (with lovely phrases such as ‘ha’porth’ and ‘his nibs’). He’s not even settled in before Raker drags him back into another case (although there is enough time for some post-traumatic stress syndrome, as he recalls escaping from a giant Ruritanian robot destroying a city).

All the usual Holmesian aspects are present. He has an Inspector Lestrade (Jarrat, although he requests Holmes’ help via a televisor – using ‘aether’, the substance once thought to fill all space that allowed electromagnetic waves to pass through it; as Raker describes it, ‘It is akin to keeping the world’s most objectionable goldfish.’). There is a Reichenbach Falls, a Moriarty, even an Irene Adler, in the form of Inanna Meyer, who turns up as an agent of the Secret Service Bureau (via Sax’s brother, Dunmow, keeping up the connection with Mycroft). But there is more attention to detail: Sax looks like the best Holmes (Jeremy Brett and Basil Rathbone) with the high forehead, thin eyes, always smoking; Watcham is a man affected by the war, and the army (at one point, he says, ‘God’s fucking balls, Raker, who killed the man?’), as well as being intelligent and literary, as his occasional journal entries suggest.

The story cracks along, filled with great dialogue and bits of Holmes analysis and little hints of other details (such as the use of Cavorite and mention of Einstein, and Ellis’ favourite detail about someone being invisible, namely that they would be blind), which all add up to a wonderfully entertaining story, told in a very appropriate black and white art style with a European sensibility but reminiscent of Victoriana. And then Ellis turns things completely around with the revelation of the identity of ‘The Man Who Wasn’t There’ and why he was killing aetheric engineers, explaining the entire conceit of the book itself and the details therein and providing the ultimate dilemma for Sax Raker. It is one of the most compelling tales Ellis has told in pure genre fiction, and shows how good he is when constructing fiction for entertainment. Highly recommended.